Technical medicine internships in the University of Twente’s master’s program

Marleen Groenier, Jordy van Zandwijk, Rob Hartman en Nicole Cramer Bornemann

Technical Medicine, University of Twente, The Netherlands

In this chapter, we will first elaborate on the rationale of the master internships at the Technical Medicine (TM) program of the University of Twente by explaining their place in the curriculum and the goals of the internships in the second (M2) and final year (M3) of the master’s program (Part 1). Next, we will describe how the M2 and M3 internships are structured, organized and assessed (Part 2). Finally, we will present future directions (Part 3). This chapter presents the perspective of the TM program at the University of Twente.

Key points:

- The master internships are an important step in the transition from student to professional, especially for technical medicine students because there are still few role models available.

- The three pillars of the curriculum are represented in each internship committee: a clinical supervisor, a technical supervisor and a professional development supervisor.

- Research and clinical activities are ideally integrated, meaning that students perform clinical activities directly contributing to the medical technical intervention they are investigating.

- Peer-to-peer coaching and professional development supervision are essential elements supporting technical medicine students’ communication skills and professional identity development.

Rationale of the Master’s Internships

The purpose of internships in the TM curriculum is to expose students to authentic, work-based learning environments. In the bachelor TM internships, students familiarize themselves with the healthcare context and the position of the technical physician. In the master TM internships, students practice the technical-medical problem-solving approach in various, authentic contexts. The repeated exposure to technical-medical practice in the internships in the second year of the master’s program grants students lots of room for personal and professional growth (Groenier et al., 2023). The characteristics of the internships also contribute to becoming an adaptive professional (Groenier et al., 2023) and shaping the students’ professional profile.

Professional profile

A technical physician will, with independent authority and based on a thorough understanding (insight) of the functioning of the human system and technology:

- perform medical-technical complex procedures;

- optimize existing medical-technical interventions;

- design and develop new possibilities for diagnostics and therapy.

When a medical intervention is highly specialized due to the involved technology, the technical physician is the most appropriate practitioner and shall be the one to apply (individually or in a team) the technological intervention to the patient. Subdividing various tasks involved in complex medical procedures should enhance treatment safety and efficiency. The professional profile of the technical physician is described in Chapter 1 (this book). Several concepts are incorporated into the master internships: 1) Independent authority; a requirement for technical physicians to meet certain quality standards, 2) Conceptual understanding; not only important for technical and medical concepts but also highly relevant concerning professional behavior. Technical physicians need a certain level of introspection and an understanding of their motives, competencies and pitfalls, 3) Insight in the functioning of the human body and technology.

It should be noted that, notwithstanding the innovative character of the work of the technical physician, there is also a place for technical physicians to perform routine clinical interventions, such as patient consultations, or implement existing medical technology, such as the implementation and evaluation of artificial intelligence into a medical imaging department.

The CanMeds framework used for defining the competencies of physicians was also used to guide the end terms of the master’s program. The CanMeds framework is an internationally recognized competency profile for healthcare professionals in general and medical specialists in particular (Rademakers, De Rooy, & Ten Cate, 2007). For the technical physician, the following roles or competencies were defined:

- Technical-medical expert

- Communicator

- Collaborator

- Organizer

- Academic

- Practitioner

Similar to the assessment of medical students and physicians in training, the technical-medical skills of the technical physicians can be assessed at five levels, from the level of novice to independent professional. In addition, the specific role of the professional indicates a kind of desired way of working or approach to clinical practice and elaborates the technical physician’s unique problem-solving strategy.

Master specializations

Students can specialize in one of two subdomains or master tracks:

- Medical Imaging and Interventions entails the field of minimally invasive technology, artificial intelligence, computer-aided interventions, the (3D) reconstruction of damaged tissue, and advanced imaging and localization techniques.

- Medical Sensing and Stimulation entails the field of the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of medical signals (diagnosis) and the adjustment of signals for improving human functioning (therapy), both in the hospital and the home situation.

In internships, students are confronted with authentic, work-based situations. This allows them to apply the knowledge and skills acquired during their studies in the real world. This has the advantage that these knowledge and skills become contextualized and students learn to adapt their knowledge and skills to a situation that enriches their repertoire of actions. In the master’s internships, students make the transition from formal, on-site education to applying and refining their knowledge and skills to novel work-based problems as well as gaining new knowledge and skills from working on challenging clinical problems in the workplace. Students undertake four 10-week internships, i.e., clinical placements in hospitals, in the second year of the master’s program and one 10-month internship in the final year. There are four consecutive TM internships with the aim that students practice the technical-medical problem-solving approach in various, authentic contexts thereby introducing meaningful variation (Mylopoulos et al., 2018). Additionally, this repeated exposure to technical-medical practice grants students room for personal and professional growth (Groenier et al., 2023). These characteristics of the internships contribute to becoming an adaptive professional (Groenier et al., 2023).

Internships in the Technical Medicine Curriculum

The Technical Medicine curriculum includes several internships in both the bachelor’s and master’s programs. In the bachelor’s program, students have two-week internships during their first (B1) and third (B3) years.

Bachelor Year 1 Internship

The B1 internship focuses on introducing students to the Dutch healthcare system, focusing on understanding the patient’s perspective. These internships are primarily held in clinical departments of hospitals, nursing homes, and care homes.

Bachelor Year 3 Internship

B3 internships provide a glimpse into the medical specialist’s perspective. Another goal is to help students discover their role as technical physicians within the Dutch healthcare system. During the B3 internship, students are encouraged to identify problems, questions, or potential innovations that they can further explore in later stages of the program, such as their bachelor’s graduation project, or during individual internships in the second and final years of the master’s program.

Technical Medical Bachelor Graduation Project

For their bachelor’s degree graduation project, students collaborate in teams of about 3-5 members on a technical-medical project or question originating from a clinical department. This marks the culmination of their bachelor’s degree and lasts 10 weeks. Within this framework, they have the opportunity to showcase their knowledge, skills, technical-medical mindset, and critical thinking in a comprehensive project related to a specific medical discipline. Like the master’s internships, where individual internships are undertaken, multiple supervisors supervise and assess the work from diverse perspectives (medical, technical, technical-medical, and professional development).

Master Year 2 and 3 Internships

The master’s internships in the second and final year of the educational program differ in several aspects from the bachelor’s internships. In the master’s internships, students are dedicated to addressing technical-medical questions aimed at directly improving patient care. These projects can result from previous bachelor’s students’ work during their B3 internships, or more commonly, clinical partners propose clinical problems that involve innovating, optimizing or implementing medical interventions with medical technology. The clinical problem can be related to diagnosis, treatment or aftercare and often involves the implementation, improvement, application or design of medical technology.

An essential feature of the M2 internship year is its structure, which consists of four consecutive internships. This structure exposes students to various challenges and experiences by rotating among clinical departments, supervisors and projects. Students can choose a broader experience in the final internship by applying for an internship at a company, a clinical department or a company-based department abroad. The diversity of M2 internships can help students determine their specialization or the direction they wish to pursue in their M3 graduation internship.

The M3 graduation internship can be considered the master’s thesis of the educational program. During this phase, students demonstrate competence in line with the professional profile of a technical physician within a clinical department.

Learning objectives M2 and M3 internships

The overall objective of the clinical internships in the second year of the master’s program is to practice the technical-medical problem-solving approach in various, authentic contexts. To this end, students have to become familiar with the nature, specific characteristics and functioning of patient care in the discipline visited, in particular concerning technical medical interventions. In addition to a general orientation in the specialist patient care of the discipline, students identify and analyze a group of patients with a specific technical-medical problem. Students should delve into the specific diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for this group of patients and where possible attend and perform them.

The goal of the third master’s year is to provide an opportunity for students to reach the required final level of Technical Medicine study. In the final year, students are expected to demonstrate that they have mastered the characteristic technical-medical problem-solving approach and that they can apply it independently as a starting professional from the perspective of clinical problems involving technology. This in no way means that students solely work on an individual basis, on the contrary, students demonstrate that they are able and willing to work in a collaborative relationship with other professionals. This is because Technical Medicine students are expected to learn to make a good distinction between when they can rely on their own knowledge and resourcefulness, or when it would be better to collaborate with, or consult, other colleagues and professionals. Technical Medicine students are expected to have ownership of the project and to take the lead in the process. Furthermore, in line with self-directed learning and adaptive expertise theories (see e.g., Kua et al., 2021; Bohle Carbonell et al., 2014; Hatano & Inagaki, 1986), students are expected to learn to direct their own learning and professional development process, which includes indicating their own need for more or less supervision. Technical Medicine students mainly work and learn in medical (academic) practice according to the principle of participatory learning (Domínguez, 2021). See Box 1 for the M3 performance criteria.

At the end of the M2 year, students should be able to demonstrate the same performance criteria as described for M3 with two exceptions:

- the required level of independence in translating a clinical problem into a technical medical question at the end of M2 is less than at the end of M3;

- in M3 students are explicitly required to demonstrate that they can effectively manage and evaluate one’s own work and education, which is not yet required at the end of year 2.

Box 1: performance criteria M3.

At the end of the M3 year, the student has demonstrated the ability to:

- independently translate a clinical problem into a technical medical question and, through further analysis and exploration, propose innovative solutions or directions for solutions;

- sufficiently grasp the specific knowledge domain (and jargon) of a clinical specialization to enable effective analysis and discussions thereof;

- delve into necessary technological knowledge and skill domains to contribute to the identification of (new) applications/solutions;

- make a scientific contribution to the technical medical field and report on it;

- establish and maintain effective relationships with patients, mentors, and personnel from various disciplines;

- demonstrate acquired clinical competencies through completed OSATS and KKB assessments;

- collaborate effectively within a multidisciplinary framework;

- plan and coordinate tasks responsibly, considering possibilities and limitations, as well as the availability of resources and personnel;

- set priorities, take control, and evaluate;

- effectively manage and evaluate one’s own work and education;

- learn deliberately from experiences and articulate these experiences.

Realization of internships: technical-medical projects and research lines

Clinical departments can apply for TM M2 and M3 students by formulating a clinical question or challenge for which the solution lies in the technical medical domain. The question or challenge is preferably quite broad but within the boundaries of the learning outcomes of the TM program. This relative freedom stimulates students to determine what they want to learn and achieve their own learning goals and objectives, apart from what the program dictates. This clinical relevance is very important, meaning that the project aims to ultimately diagnose or treat a patient better, faster, safer or more efficiently. The department also provides adequate opportunities for the student to gain clinical experience, ideally with a direct relation to the proposed clinical question. The possible clinical activities within the department are mentioned in the internship description, so students can (also) choose an internship site based on what they want to learn and experience clinically.

Structure, Organization and Assessment of Master Internships

The organization and current state of the year 2 master internships (M2) are first described and after that the organization and current state of the year 3 master internship (M3).

M2 Internship Sites

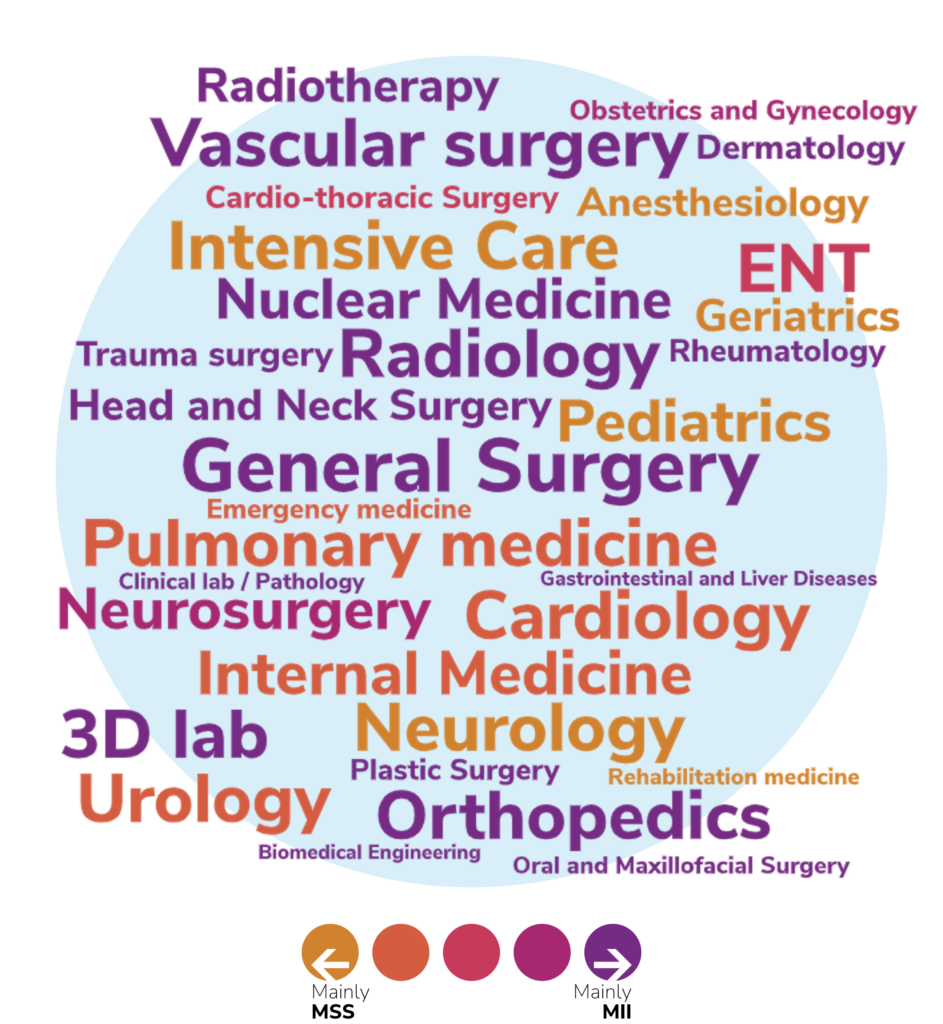

The four 10-week internships are usually in a clinical department at either an academic hospital, at one of the Collaborative Top Clinical Training Hospitals (STZ), within a nursing or home care institution, or at a medical technical company. Figure 1 gives an overview of the M2 internship sites and in Figure 2 the various topics are visualized.

M2 Internship Process and Milestones

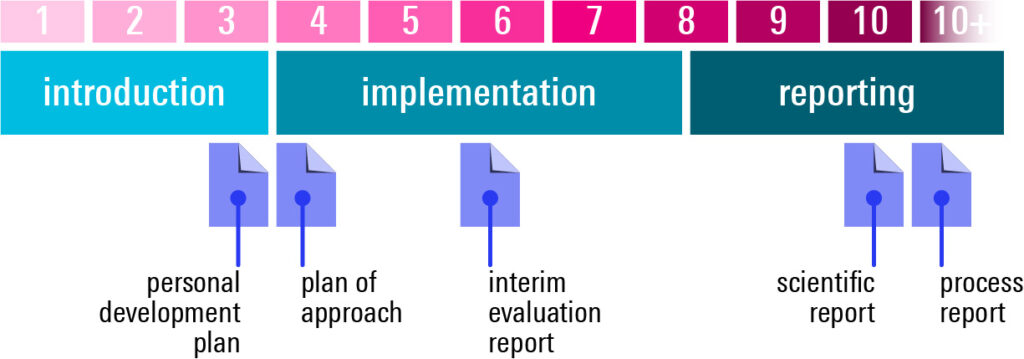

Each internship has a fixed structure with an orientation phase in which the student writes a plan of approach and professional development plan, the implementation phase for carrying out the project and a reporting phase, see Figure 3.

Before the internship, students should become acquainted with the current projects and associated research line(s) of the department such that they can discuss which aspect they want to contribute to. The internship starts with an introduction to the daily practice of the department. In these first two to three weeks students familiarize themselves with the clinical department, and the relevant anatomy, (patho)physiology and technology by participating in the clinical practice of the department and through literature research.

After the project’s content and clinical activities have been discussed with the supervisors, students write a plan of approach for the project and clinical activities as well as a professional development plan for the professional and personal learning goals. In the plan of approach, students describe the technical medical question and specify the activities required to answer this question. In addition, students use the plan of approach to elaborate on the planned and agreed-upon clinical activities. This plan of approach is submitted for approval by the supervisors within 2-3 weeks from the start of the internship. Students also write a professional development plan containing the students’ individual learning goals for that particular internship which is assessed by the professional development (PD) supervisor.

The implementation phase takes up (more than) half of the internship duration. In addition to clinical activities, students use this phase for working on the project, e.g., by doing literature research, collecting data, analysing measurements, etc. and working on their own learning goals.

Halfway through the M2 internship, students reflect on the progress of the project and their professional development by writing an interim evaluation report. Also, the internship office requests the supervisors to evaluate the progress of the student and report any circumstances that might interfere with the timely completion of the internship. The aim is to strictly adhere to the aforementioned structure for at least the first and second M2 internship of the student.

In the final internship phase, students wrap up the internship by reporting on their activities. This mainly consists of a scientific design or research report documenting the project activities and results. In the M2 internships, students also write a professional development report in which students evaluate and reflect on their personal learning goals and describe their professional and competence development. Lastly, students also present the clinical relevance and impact of their projects at the internship department.

Students are expected to spend approximately half of the time working on the technical-medical problem of the project. The remaining half is spent on clinical activities. In practice, this means participating in patient handover, patient consultations, large ward visits, assisting with surgery and outpatient clinics. Many students regularly assist with interventions and perform consultations at an outpatient clinic. Performing reserved procedures always takes place under supervision.

M2 Guidance and Assessment

In the workplace, students are supervised by a clinical supervisor, usually a medical specialist. A technical supervisor from the university safeguards the level of technical innovation and the PD supervisor from the university monitors the students’ professional development. Increasingly, technical physicians from the clinical departments are involved in the supervision of TM students. The technical and clinical supervisors change per TM internship, but students keep the same PD supervisor for two years.

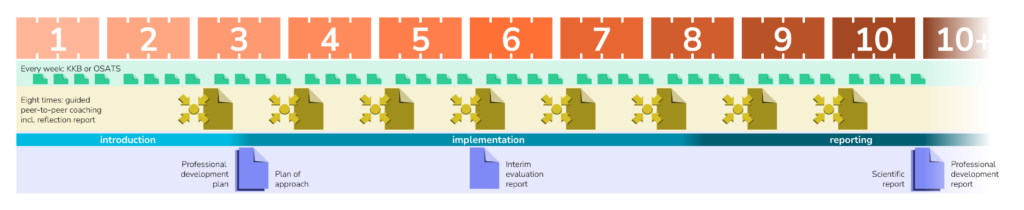

During the internship year, students return to the university every other Friday for formal, on-site education. Guest lecturers teach about specific topics that are relevant for the internships and there are guided peer-to-peer coaching moments with other students and the PD supervisor.

M2 internships are assessed on different aspects: 1) working on the technical-medical project, 2) performing clinical activities, 3) and professional development. Students write a scientific design or research report about the technical-medical project. As proof of the obtained clinical experience during an internship, the student is expected to collect at least 10 performance-based assessments (i.e., KKB and/or OSATS, see paragraph 2.9) per internship. Furthermore, students write a reflection report about their professional development and the development of TM competencies.

M2 Peer-to-peer coaching

The broader goal of the internships is for the students to position themselves in the healthcare environment and demonstrate the ability to collaborate with other professionals on challenging technical-medical problems. Creating a safe learning environment at the educational institution where students are supported in this professional development process is crucial for learning and adaptive expertise development. During the M2 internships, guided peer-to-peer coaching is used to this end. Guided peer-to-peer coaching often has a set structure (Van den Ende, 2017) where a group of students delves into a problem or question of one of the participants. In these sessions, the PD supervisors encourage a critically reflective work attitude. This allows students to learn from past experiences so that similar situations do not just happen to them in the future, but that they learn to act proactively as professionals.

The regular guided peer-to-peer coaching moments with the same PD supervisor in a safe learning environment, away from daily practice, stimulate technical medicine students’ awareness of their own qualities, positioning and professional role. Because technical physician role models are limited in clinical practice, students often face situations where they will have to explain the role of technical physician in general in the healthcare system. Also, the Individual Healthcare Act (BIG in Dutch) requires that technical physicians can monitor, assess, and adjust their professional behavior themselves (see also Chapter 1). In these peer-to-peer coaching moments, students recognize similar struggles and dilemmas, have in-depth discussions about internship experiences and reflect critically on personal and professional development. These guided peer-to-peer coaching moments support further adaptive expertise development by promoting self-directed learning and reflection on personal and professional development (Kawamura et al., 2020; Kua et al., 2021).

The advantage of four consecutive internships is that students can try out new ways of working and learning from them in different contexts with different supervisors and colleagues in the workplace. This gives students room for self-directed learning and personal and professional growth. It also means that if a way of working does not work out as planned, there are other internships to practice with a different approach and failing is an option.

M3 Internship Sites

In the third and final master’s year, students perform a clinical specialization internship, during which the master’s thesis will be conducted within an approved clinical department of a Dutch or foreign hospital. The distribution of M3 internship sites is similar to the M2 (see Figure 1), only in M3 there are no internships at companies and fewer internships abroad.

M3 Internship Process and Milestones

An M3 internship lasts 40 weeks full-time, to be completed within 12 months. A shorter internship period than 40 working weeks is not allowed. The intention is that the student makes full use of the 40 weeks for clinical development. Similar to an M2 internship, the M3 internship has a fixed structure with an orientation phase in which students write a plan of approach and professional development plan, an implementation phase for carrying out the technical-medical project and, finally, a reporting phase, see Figure 4.

During the master’s graduation internship, resulting in a thesis, students have to show to both function on an academic clinical level, as well as contribute to the applied scientific (medical technological) research or design projects from the clinical department. Next to a test of competence, the learning effect is important as well: the student did not work this independently on an academic level before, surrounded by medical specialists who have earned their spurs in this field.

Approximately halfway through the internship, i.e., 20 weeks after the start of the internship, students’ progress is evaluated. The supervisors are asked how they assess students’ progress and whether they expect any problems concerning graduation. The PD supervisor monitors this interim evaluation process and, if necessary, takes the initiative to discuss the situation and take measures if needed.

M3 Guidance and Assessment

After agreement with the supervisors, a graduation committee, appointed by the TM Examination Board, is responsible for further guidance and assessment of the student. The M3 graduation internship can only take place at a hospital department that has shown enough experience in supervising TM students, through the Bachelor and M2 internships. The same accounts for the clinical and technical supervisors. The graduation committee consists of at least four members from the various disciplines related to the technical-medical domain: medical, technical, technical medical and professional development.

Assessment of an M3 internship is based on: 1) thesis, 2) thesis defense, 3) scientific reasoning, 4) clinical activities and reasoning, and 5) professional development. To monitor the quality of the assessment, an independent external member is added to the graduation committee at a later stage. This member is often a researcher who has been affiliated with a different research group than where the technological supervisor of the student is embedded. The external member assesses the final product and the defense. The graduation report (the thesis and professional development evaluation) primarily informs the graduation committee about the completed graduation assignment.

M3 Peer-to-peer coaching

Like M2 internships, in M3 internships students have peer-to-peer coaching supervised by the PD supervisor (see paragraph 2.3.1). However, students in an M3 internship meet less frequently with their peers, about every five weeks, and in every other peer-to-peer coaching meeting the PD supervisor is present. This means that students have more responsibility in monitoring their professional development and are expected to coach each other during unguided peer-to-peer coaching meetings.

Clinical and technical-medical activities: feedback and assessment

In both the M2 and M3 internships, technical medicine students need to develop and monitor their development of clinical, technical-medical skills related to the technical-medical questions and innovations they are working on. To monitor students’ clinical development in the M3 phase, several methods and tools are available.

Concerning the end terms of the technical medicine educational program, the professional roles (see paragraph 1.1) of technical-medical expert and practitioner are most relevant in describing the level and amount of clinical activities that students must undertake to fulfill program requirements. A portfolio is built over time during the M2 and M3 phases, summarizing clinical activities related to the different professional roles and feedback provided by supervisors.

An important aspect of acquiring these feedback forms, based on the clinical activities and experiences of our students, is that they are all integrated as much as possible with the technical-medical questions and innovations they are working on as part of their M2 and M3 internships. Ideally, this results in, on the one hand, a significant gain of clinical experience for the students, and on the other hand, it demonstrates how technical physicians could fit in a particular department and what their added value would be to the clinical team or department. The evaluation forms provided by the educational program come in two formats: a concise form known as a ‘brief clinical assessment’ (Dutch: KKB), and an extended form that is based on the reserved procedures that technical physicians are allowed to perform independently, according to the Healthcare Professionals Act (Dutch: Wet BIG), known as an objective structured assessment of technical skills (OSATS). The original developers of the OSATS, Martin et al. (1997), define technical skills as specific surgical, operative skills. A rating scale is often used to assess these technical skills, consisting of items such as time and motion, instrument handling, and knowledge of instruments. Both KKB and OSATS forms serve as formal tools for students to acquire clinical feedback based on their actions and clinical reasoning.

As part of the substantiation of clinical development, students need to account for at least forty evaluation forms per internship year (forty in both M2 and M3). Through this feedback, students can determine and shape their own direction of clinical development and demonstrate their progress. Currently, there is a diverse domain where clinical feedback can be acquired, providing students with significant autonomy to shape their clinical development. The final requirement of acquiring forty evaluation forms (either KKB/OSATS) each internship year and when or how they are acquired is left to the discretion of the student.

Future Directions

Throughout the history of technical medicine, the clinical internship has evolved into situations where students have the opportunity to explore, innovate, and develop their final skills, insights, and attitudes to become full-fledged technical physicians. Due to historical reasons, these situations in which students immerse themselves in the healthcare environment during the last two years of their education encompass various disciplines and perspectives. Often, these perspectives converge from clinical, technological, and professional perspectives into that of the technical physician. Consequently, the circumstances under which students undertake their internships involve separate medical, technological, and professional supervisors.

With over 600 graduated students in 2021, the capacity to train technical physicians in the field has increased significantly, leading to a more frequent occurrence of technical physicians being trained by their peers in practical settings. Whereas the role of the technical physician on the work floor was initially minor, the profession has now reached a certain level where the primary responsibility for training often lies with (senior) technical physicians in the field. Educational programs in technical medicine should, therefore, strive to leverage the practical situations occurring in the field, where future technical physicians are increasingly trained by their counterparts in real-world settings.

Building upon the previous point regarding granting more responsibilities to technical physicians in the field, the challenge arises of further incorporating and integrating all the practical experiences of M2 and M3 internships. Historically, internship content consisted of two parts: one focused on gaining clinical experience and the other on addressing a medical-technical (research) question. Looking ahead, the goal should be to integrate these parts as much as possible in practice. This integration will enable technical physicians (in training) to actually add value to a clinical department.

While integration has occurred naturally in numerous instances, many internships still involve separate parts. While this setup may offer valuable learning experiences from different perspectives during the M2 phase, integration should become integral, particularly during the M3 phase. Moreover, increased involvement of technical physicians as main or daily supervisors, rather than solely focusing on research-oriented supervisors, will further enhance this integration.

References

Bohle Carbonell, K., Stalmeijer, R. E., Könings, K. D., Segers, M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2014). How experts deal with novel situations: A review of adaptive expertise. Educational Research Review, 12, 14-29.

Domínguez, R.G. (2012). Participatory Learning. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1903

Groenier, M., Walter, E., Helfenrath, K. & Swennenhuis, P. B. (2023). Veiligheid en risico: voorwaarden voor adaptieve expertise ontwikkeling?! Onderzoek van Onderwijs, 52(3), 28-30.

Hatano, G. & Inagaki, K. (1986). Two courses of expertise. In: Stevenson, H. W. & Azuma, H. (eds) Child Development and Education in Japan. W. H. Freeman & Co., pp. 262-272.

Kawamura, A., Harris, I., Thomas, K., Mema, B., & Mylopoulos, M. (2020). Exploring how pediatric residents develop adaptive expertise in communication: the importance of “shifts” in understanding patient and family perspectives. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 1066-1072.

Kua, J., Lim, W. S., Teo, W., & Edwards, R. A. (2021). A scoping review of adaptive expertise in education. Medical Teacher, 43(3), 347-355.

Martin, J. A., Regehr, G., Reznick, R., Macrae, H., Murnaghan, J., Hutchison, C., & Brown, M. (1997). Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. British Journal of Surgery, 84(2), 273-278.

Mylopoulos, M., Kulasegaram, K., & Woods, N. N. (2018). Developing the experts we need: fostering adaptive expertise through education. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 674-677.

Rademakers, J. J., De Rooy, N., & Ten Cate, O. T. J. (2007). Senior medical students’ appraisal of CanMEDS competencies. Medical Education, 41(10), 990-994.

Van den Ende, M. (2017). (Begeleide) intervisie. Bijblijven, 33, 487-497.